Source: Vertu

- Manufacturer of over-priced bling phones goes bankrupt

- "It's the Age of Austerity so let's sell jewel-encrusted handsets." Great idea

- Company had changed hands three times since 2012

- £128 million in debt but creditors offered just £1.9 million - with the inevitable result

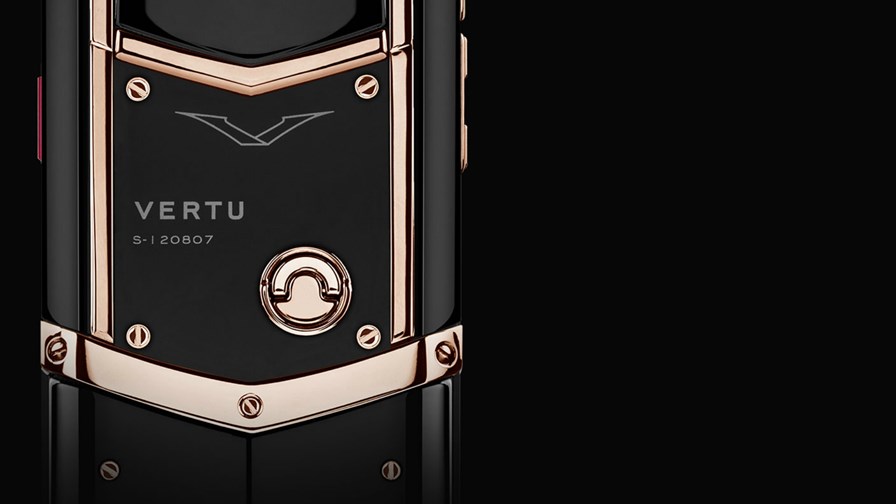

Vertu's USP and brand value (if you can call them that) was as a purveyor "of the finest luxury mobile communications instruments handmade by our craftsmen in England using the most exquisite materials and cutting edge technology" and other such fatuous, over-egged trumpery.

Vertu's handsets were certainly well made (although they unfortunately featured hand-stitched snakeskin and ostrich leather covers in various bilious shades) and they might have been assembled using cutting edge technology but the phone's innards were decidedly dated. They encapsulated outmoded Android technology and processors based on specifications for massed produced handsets of yesteryear.

However, marketed to people with considerably more money than sense, technology was secondary to them being reassuringly, indeed, ludicrously expensive and thus unattainable by the hoi polloi. Prices for Vertu's Signature suit of handsets ranged from a starting price of £11,100 through to £39,100 for one model "featuring pure jet red gold", whatever that is.

The Signature range was introduced in 2003 with a keypad loaded with 5 carats of ruby bearings but the last model the company introduced was the Signature Touch in 2015. Vertu also made "limited edition" handsets for the likes of Bentley and Ferrari. Individual clients could have their handsets loaded with their own exquisite choice of customised bling and ownership of a Vertu handset came with "lifetime access to "a 24-hour concierge". In reality that lifetime has turned out to be remarkably short. No concierges are answering Vertu phones today leaving their devastated owners to source their own hair dye, shoe lifts and escorts.

Not for nothing have Vertu handsets been called "tasteless trash" by Wired magazine and "technologically modest" by the traditionally understated Financial Times.

Vertu has not filed a financial statement since 2014, when it posted a £53 million loss on sale of £110 million. The company claimed to have sold 450,000 of its handsets around the world at an average price of US $9,000 each.

Business model based on minimal volumes at massive prices. Not a recipe for success

It was evident that Vertu, making tiny volumes of handsets at unfeasibly high prices, was pursuing a doomed business strategy, but the company had recently done a mysterious 'smoke and mirrors' technology sharing deal with TCL of China, the PRC conglomerate which makes TVs for Samsung of Korea and mobile handsets for the likes of Alcatel and BlackBerry. Details are sketchy and unclear but the nub of it seems to be that $40 million dollars have been paid by someone, somewhere to someone else, somewhere else, in an agreement that would have seen TCL technology being included in the next run of 30,000 bling-laden handsets. Obviously this will now not happen but where the money came from and went to remains unclear.

Back in the real world, some 200 workers at Vertu's UK factory in the little town of Church Crookham in Hampshire, England have lost their jobs. They were already owed unpaid salaries and contributions have not been received by the pension funds. Suppliers too are owed money, from chip manufacturer Qualcomm all the way through to the local rubbish removal company.

Meanwhile, Hakan Uzan, who offered to pay just £1.9 million to buy Vertu out of its £128 million administration, (a ploy that failed) , says that he retains ownership of of the Vertu brand, technologies and licenses and that a new company will, in due course, rise, phoenix-like, from the ashes of the old. And this despite the fact that Gary Chen, the main man behind in Godin Holdings in Hong Kong, who sold Vertu to Hakan Uzan, is suing him for holding Vertu shares without having gone to all the fuss and bother of paying for them.

It's hard to find out what is really happening with Vertu. The defunct company's website continues to work for now and carries a statement saying, "We have taken the difficult decision to suspend our current Vertu services and focus on developing a completely new, next generation suite of services, exclusively for our customers."

This is the sort of outrageous spin that would have Baron Munchausen, the fictional 18th Century German fantasist, spinning in his grave at 10,000 revs per minute out of envy at the unmitigated blatancy of it. The reality is that Vertu has gone bankrupt owning hundreds of millions of Pounds, has almost no tangible assets, no workforce and no known access to credit.

The website signs off with this: "We plan to launch these new services from September 2017 [i.e. in two months time!!] and will update this page closer to the launch with further information. Anyone waiting with bated breath for the pending momentous announcement will probably have asphyxiated long before then.

A business dynasty stripped of its assets and in exile in France

Vertu was a company with a chequered history. Formed in 1998, it was originally a part of Nokia during its glory years but was spun out of the by then greatly diminished Finnish company in 2012. It went first to EQT VI, a Swedish private equity company for £175 million and then, in 2105, passed to Godin Holdings of Hong Kong. The purchase price was not disclosed. Finally Vertu was bought for £50 million in March 2016 by a company fronted by Hakan Uzan, a Turkish exile in Paris

Hakan Uzan was born into the once-influential Uzan dynasty who ran the Uzan Group, an industrial conglomerate headquartered in Turkey. The group's assets included a bank, several electricity generating stations, a number of broadcasting outlets and the mobile carrier Telsim (which was founded in 1994 with a huge loan provided by Nokia and Motorola). Telsim over-extended itself and then found itself in extreme financial difficulties when the dotcom bubble exploded. In 2001 it defaulted on debts of $2.7 billion and creditors and institutional investors sued the Uzan family, and duly won billions of dollars in damages.

It was the beginning of the end for the Uzans. in 2004 the Turkish state seized 211 Uzan group companies. The government sequestered the various enterprises and sold them to help defray the $5.7 billion in debts run up by the Imur bank, which belonged to the Uzan family. At that point several leading members of the family left Turkey and 'went into exile' claiming that they were the victims of a political witch hunt. Most settled in France.

Email Newsletters

Sign up to receive TelecomTV's top news and videos, plus exclusive subscriber-only content direct to your inbox.